Forward by Dale Carter, security director of The RINJ Foundation.

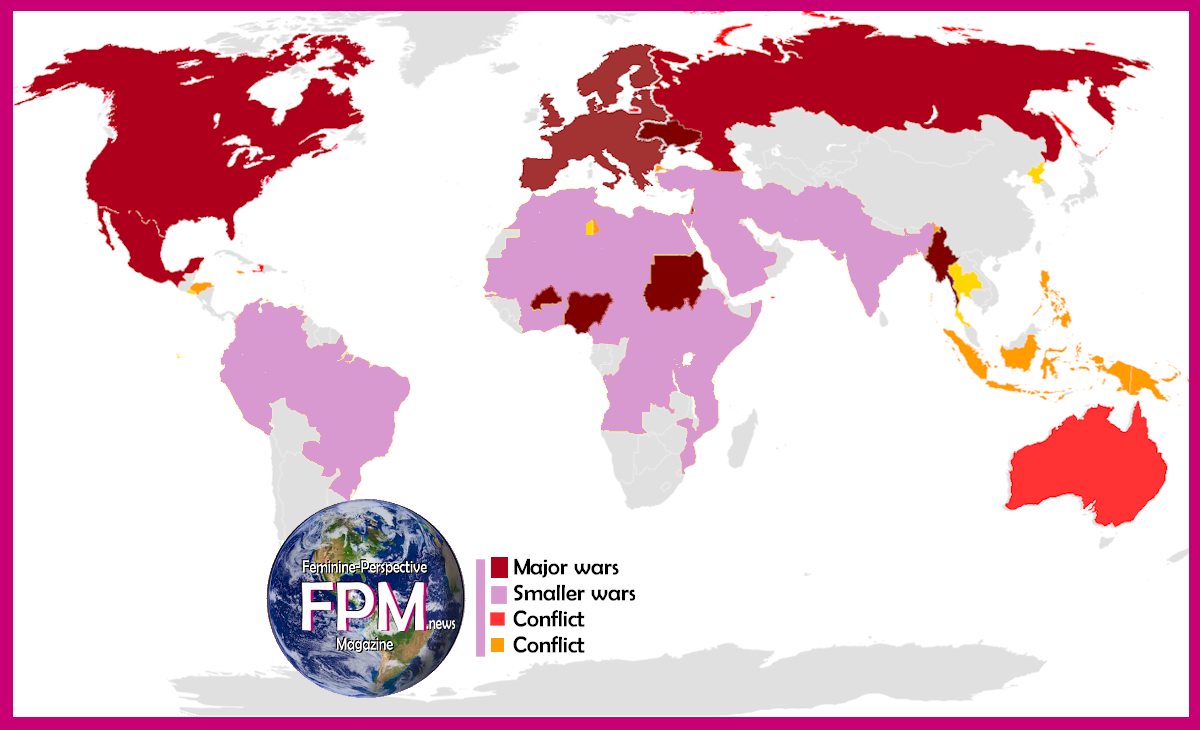

“No news or articles about the Ukraine war should exclude this warning about cluster munitions. In the civilian areas of the war zone, which is by the way, largely an urban war, there are massive efforts to support women and children left behind by the men and their war fighting. Marked facilities include women’s shelters and family health care. This map marks many of those areas on behalf of The RINJ Foundation and its various humanitarian sub units and civil society partners with an “R” roundel. These are no-bomb areas and that especially relates to cluster munitions. The Ukraine warriors have been using cluster munitions in Ukraine and Donbass since 2014, literally slaughtering women and children. This must stop. Many regions are now uninhabitable because of these quasi-mines which kill mostly children.Please share this message.”

No bomb civilian regions and NGO family support centers.

No bomb civilian regions and NGO family support centers.

Click to enlarge. Cluster munitions are to be used in the densely populated war zone region areas shown here with the “R” Roundels according to sources in Kiev. Map is an adaptation of a work by Mapbox and unocha.org. Art / Cropping / Enhancement: Rosa Yamamoto / Feminine-Perspective-Magazine and RINJ shelter/clinc data by Geraldine Frisque of The RINJ Foundation

A Ukrainian soldier prepares to fire a Russian TOS-1A Solntsepyok heavy flame-thrower rocket launcher, captured by a Ukrainian army battalion, towards Russian positions on the front line near Kreminna, Luhansk region, in July 2023.

Photo credit: AP Photo/Libkos

By James Horncastle, Simon Fraser University

Editorial Note: This article is an opinion piece that contains learned speculation that may not reflect the reality we see on the ground in Ukraine and Donbass.

In the weeks leading up to the official launch of the Ukrainian counteroffensive against Russia, various media commentators and officials hyped the potential success of the operation.

This emphasis on success, however, created unrealistic expectations about its military potential.

Russia has had several months to prepare for the Ukrainian counteroffensive. Extensive fortifications, including trench systems reminiscent of the First World War, make any rapid advance difficult. Overcoming such a defensive system without specialized equipment, which Ukraine lacks, means that progress will be slow and casualty-heavy.

Ukraine, furthermore, is not fighting the same army it did in 2022. The Ukrainian army still possesses a qualitative advantage over the Russian army. That disparity, however, is less than it was in the past.

Russian forces, in fact, have learned from past failures and have displayed an ability to perform increasingly complex and effective tactics.

A variety of tools

Currently, there are at least four distinct formations that Ukraine is relying on for success in the counteroffensive. While these forces are focused on defeating Russia, interservice rivalry is sometimes a problem.

The Ukrainian army remains the bedrock of Ukraine’s fight against Russia. The best-known formations are the army’s battle-hardened units who maintain tactical advantages against the Russians. These units, however, have suffered significant casualties since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Supplementing them are recently constituted western-trained and equipped brigades. Some of these units have a technological advantage over the Russian forces. However, they largely consist of new soldiers, so given that they have limited equipment and are newly formed, their battlefield efficacy remains unknown.

The National Guard of Ukraine was crucial in Ukraine’s initial defence efforts. In particular, the controversial Azov Regiment served as one of the primary defenders of Mariupol.

The relative successes of the Azov Regiment, despite largely being destroyed in Mariupol, led to its reconstitution and expansion to a brigade in early 2023.

The unit’s performance prompted the Ukrainian Ministry of the Interior to create multiple brigades mirroring Azov’s force structure and tactics.

A separate formation — the Ukrainian Territorial Defense Forces — descends from volunteer battalions formed in 2014. These units are quite effective at defensive operations due to their organization within specific communities and local knowledge. Their offensive capabilities, however, are more limited.

Lastly are the Ukrainian Special Operations Forces. These forces have helped shape the battlefield, conducting raids and attacks to make conventional operations easier. By design, however, they have limited abilities to directly seize territory.

Soldiers of the Azov brigade sit in a trench near Bakhmut in the Donetsk region of Ukraine in February 2023.

(AP Photo/Libkos)

Differing military traditions

Units with varied traditions can provide tools and abilities that some armies might otherwise lack. Employing different groups of soldiers also enhances the co-ordination needed, particularly in offensive operations. Russia’s success with the Wagner Group around Bakhmut — prior to the fleeting uprising against the Russians by its leader — ably demonstrates this point.

One of the observations from defence experts is that there are parallel military traditions in conflict in Ukraine: one western-inspired, one Soviet. Western training, particularly in small-scale actions, played a key role in Ukraine’s initial successful defence against Russia’s invasion.

Western and American training gave Ukraine capabilities that it otherwise wouldn’t possess. But the basis for much of this training — American military doctrine — has several underlying assumptions. One is that armed forces possess air superiority.

This underlying assumption undermines Ukrainian efforts in two ways. First, Ukrainian counteroffensive efforts appear to be based on employing western-trained and equipped units in a breakthrough capacity. Without air superiority, Ukrainian forces are required to use their limited artillery shells to suppress Russian positions and troop movements.

The controversial decision by the U.S. to give Ukraine cluster ammunition may resolve this issue in the long term. The decision, however, likely won’t address Ukraine’s shortfalls in air superiority in time to aid the counteroffensive.

Second, this inherent requirement of U.S. military doctrine creates pressure for something western countries want to avoid in the short term: equipping Ukraine with F-16s. NATO countries have committed to training Ukrainian pilots. They have not, however, taken substantial steps to providing the F-16s themselves.

A Romanian Air Force F-16 military fighter jet, front, and Portuguese Air Force F-16 participate in NATO’s Baltic Air Policing Mission operation over the Baltic Sea in Lithuanian airspace in May 2023.

(AP Photo/Mindaugas Kulbis)

The politics of war

War, as the famous war theoretician Carl von Clausewitz famously emphasized, is an act of politics. Given the factors listed above, the slow pace of the Ukrainian counteroffensive shouldn’t come as a surprise. That pace doesn’t signal, however, that military success for Ukraine is impossible.

What matters from a political standpoint is how one defines victory. The absolute victory sought by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and others is, however, probably impossible.

But Russia and its president, Vladimir Putin, must also confront the fact that their war in Ukraine is unlikely to meet all their objectives.

Continued military operations by Ukrainian forces and their incremental success could place Ukraine in a better position should a negotiated settlement become possible.![]()

James Horncastle, Assistant Professor and Edward and Emily McWhinney Professorship in International Relations, Simon Fraser University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. \