It is sometimes maintained that the Navalny affair – his poisoning by the FSB, his arrest on his return to Moscow, and his conviction to more than two and a half years in a penal colony – would have been an opportunity for certain Western leaders to become aware of the reality of Vladimir Putin’s regime.

We can to a certain degree doubt this. It was perhaps the straw that broke the camel’s back after a multitude of other acts, with the paradoxical risk that this case would become the tree hiding the forest – the criminal nature of the regime itself.

Why now?

A question immediately arises. It is neither rhetorical nor trivial, but plunges deep into our collective consciousness, like a torment. Why now? Why about Navalny? Why almost 21 years later?

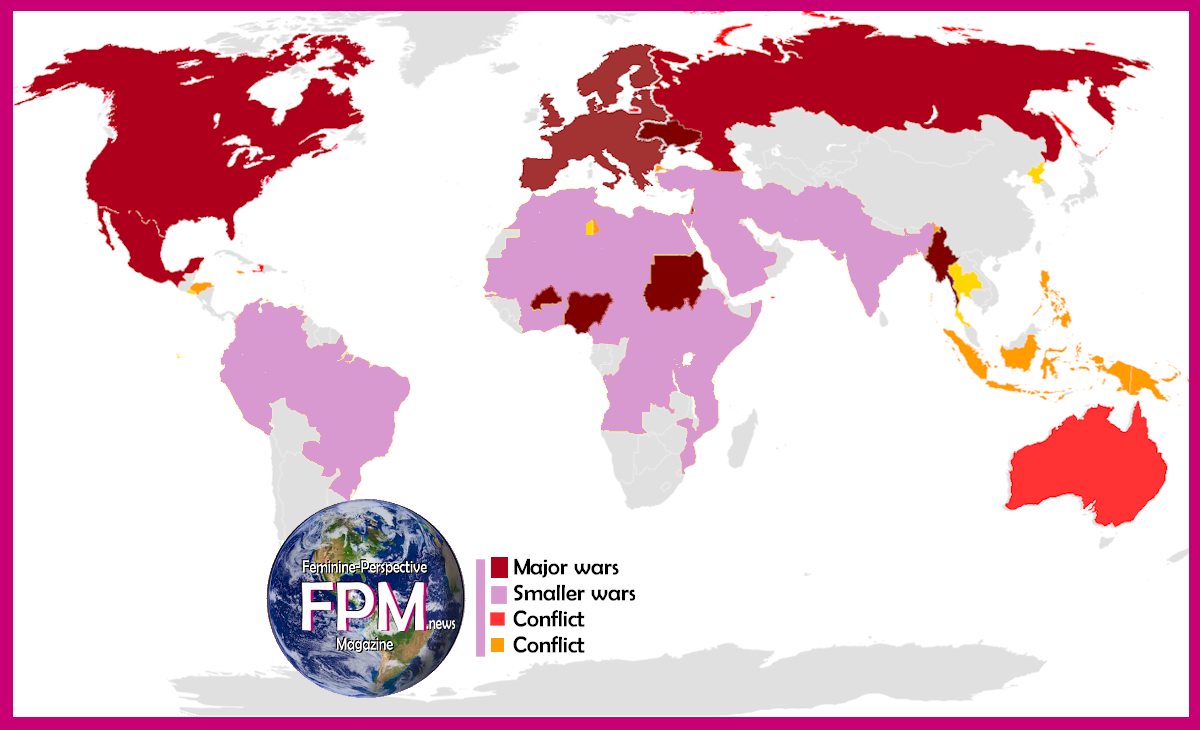

Everything seems to happen as if there had been no Chechnya, quickly out of the field of indignation. As if there hadn’t been Georgia, where 20% of the territory is still occupied de facto by Russia, and where, as the European Court of Human Rights recently ruled that war crimes have been committed. As if Ukraine had not been invaded and part of its territory, the Crimea, annexed. As if Moscow had not committed assassinations on European soil, with incredibly measured responses by the countries concerned. As if there had not been in Russia itself hundreds of assassinations for which the regime can hardly be exonerated.

As if – above all and also first and foremost – there had not been Syria, the unquestioning support for a regime guilty of crimes against humanity and 700,000 deaths, and the war crimes committed by Russian forces against Syrian civilians. Let us never forget, Putin’s regime murdered more than ISIS. Now, what Western leader would have dared to shake the hand of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi?

As if we were pretending to ignore the direct link between Putin and his services and the pure and simple organized crime remarkably brought to light by Catherine Belton’s indispensable book, Putin’s People. As if Putin’s illiberalism was not just a verbal ideology and not the instrument for legitimizing his crimes.

In sum, to declare, as Josep Borrell did after the fiasco of his visit to Moscow, that Europe and Russia are taking divergent paths and that the latter does not want a dialogue is an observation that is as accurate as it is belated: this has been the reality for more than a decade.

So why Navalny? Not because of the many barely concealed lies of the Russian regime. We have already seen them at work during the MH17 affair, the use of chemical weapons in Syria, the invasion of Ukraine or the attempted assassination of Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia.

Not because of the assassination attempt itself: Baburova, Markelov, Politkovskaya, Estemirova, Magnitsky, Nemtsov did not get a tenth of the reaction that Navalny has. Not because of the parody of justice, so common and ancient to strike dissidents. But because Navalny was able to rally millions of Russians to his fight against corruption. Even if he hasn’t been able to bring Putin down, he was able to make him stagger and ridicule him in public. Perhaps some Western leaders now realize that Putin did not embody Russia.

Is change possible in Russia?

But what exactly can we hope for?

First, let us have no illusions: the extent of Putin’s repressive system and its total blockade of the electoral process hardly suggest that he will fall by the pressure of the streets despite the decline in opinion in his favor. The latest demonstrations have been repressed with unprecedented intensity both in terms of violence and condemnation by a justice system that is under Putin’s full control. He has the security means to continue without any limits.

The same goes for the argument of demographics and brain drain, which are the subject of dark scenarios, the economy in a state of collapse and social catastrophe. At the beginning of 2011, we had already concluded that Russia would disappear as a great power within 30 or 40 years, but that does not take away from its destructive power here and now. This will not prevent Putin from remaining in power, if he has the physical capacity to do so, until 2036.

Finally, it is difficult for a regime marked by the grip of crime at all levels to evolve toward a democratic and transparent system. The number of people at all levels who have a personal interest in maintaining the system is too great. These same people have everything to lose to an independent justice system that would shed light on their actions both in terms of repression and illicit enrichment.

Beyond operational support to Ukraine and the people of Belarus, sanctions are the most effective lever of the West if it intends to support a regime change. First of all, sanctioning Putin’s relatives sends them a signal: they will be able to abandon him all the more easily as his remaining in power is detrimental to their interests. Then, we will have to accompany a transition in a pragmatic way, including through the restitution of property, by guaranteeing a partial erasure of past crimes. The punitive action of justice will have to be focused on crimes, while at the same time – as in any “justice and reconciliation” process – it will have to be carefully managed.

Finally, we will have to accompany, in a less dogmatic manner than in the Yeltsin years, the transition to a prosperous and free economy while strengthening the social safety net, which is more urgent than ever for the Russian people.

But are we ready to take this peaceful action in the aftermath?

Imperfect awareness, incomplete action

However, should we expect a major and decisive change on the part of Western countries? Perhaps we should, for a second, return to Syria. The fact that democratic leaders have not grasped the nature of Putin’s regime leaves us perplexed. The invasion of part of the Ukrainian Donbass and the annexation of the Crimea were certainly worrying events. The former reflected both a reaffirmation of the will to re-establish zones of influence and to decide unilaterally on the destiny of a state, closing to Ukraine all avenues of integration into the EU. The second was the first “rectification” of borders in Europe since Hitler’s annexation of the Sudetenland.

But the intervention of Russian forces in Syria starting in the fall of 2015 marked something else: the assertion that a permanent member of the UN Security Council could commit war crimes on a massive scale, likely to lead to the prosecution of those responsible before the International Criminal Court, without any designation or direct condemnation by the democracies. Similarly, through its 16 vetoes, most often with the support of China, Russia prevented both the delivery of independent humanitarian aid to refugees and the condemnation of the crimes against humanity of the Assad regime. In doing so, it has eroded the very notion of these crimes in the minds of Western leaders and opinions, despite the fact that they are the foundation of our historical consciousness.

What would a new alarm about Navalny be worth if it did not make an uncompromising examination of our past misdeeds? If we become firmer now without understanding how we have failed, especially on Syria, we will have remained in the middle of the ford.

There is hardly any difference between the older convictions and sanctions, especially on Ukraine or the Skripal affair, and the current declarations and especially the limited sanctions, the principle of which was decided by the Foreign Affairs Council of the EU on February 22, 2021. Admittedly, this is the first time that the Union has made use of its new sanctions regime known as “Magnitsky”, and this is a welcome precedent.

Others consider that Josep Borrell’s words, in retaliation for his public humiliation during his February 8 visit to Moscow, insisting on the confrontational position sought by the Kremlin, go further than previous statements by European officials. For his part, Joe Biden recognized in the clearest terms for an American president the global danger posed by the Kremlin regime.

However, the results are counted in terms of action: Germany has not renounced Nordstream 2, which any one serious recognizes both the danger for the EU and Ukraine and the strategic advantage it would give to Moscow, also granting it additional resources to finance its external aggression and propaganda actions. With an overwhelming majority, the EU Parliament thus called for the project to be halted. However, the rest of the EU did not unite to force Germany to do so, and to this day, some are alarmed at Washington’s less firm position in terms of sanctions.

It is therefore difficult not to accredit the hypothesis of an imperfect awareness of the nature of the threat and the depth of its penetration within part of the European elites, which would explain the timidity of the action.

Why are we weak?

Three reasons can explain this timorous character.

The first is a form of corruption of the spirit in certain circles close to power in a range of European countries. Working for a Russian company, even as a former high-ranking politician like Gerhard Schröder, is not necessarily illegal. Nor is receiving remuneration for shares in companies close to the Russian power structure if you are not or no longer a public official. Even in French law, the borderline between lobbying, consulting and influence peddling is sometimes difficult to understand.

In most European countries, private research centers or think tanks can also legally receive money from a foreign power without being required to reveal it. While European journalists are generally subject to a code of ethics that prohibits receiving such money without revealing its origin, it is not easy to enforce it. So far, however, most European countries seem reluctant to tighten their legislation, to demand full transparency or even to conduct investigations. This makes political circles potentially subject to this type of action by dictatorships.

The second reason remains the lack of direct knowledge of the nature of the Russian regime on the part of the leaders’ advisers – the Biden administration being a notable exception. This leads to inappropriate narratives, based in particular on a romantic apprehension of Russia based on historical, geographical and cultural data and not on political analysis. It is no coincidence that some soft propagandists seek to sell these old geopolitical whims to justify a new engagement with the Kremlin. This unintelligence of the regime has led to adventurous and unsuccessful attempts at re-engagement, the primary result of which is to weaken, divide and thus threaten Europe. The same advisers do not seem to be trained in any way in how unfortunate stories can feed propaganda.

A third reason illustrates this point: a common diplomatic practice leads some officials to separate the subjects. We find a trace of this in the remarks of Josep Borrell, who can say in the same sentence that one can be firm with Russia on its violations of fundamental rights and its threats against Europe and, at the same time, pursue cooperation on, for example, the environment and health. This discourse is also frequent toward China. However, when it concerns a dictatorial regime accustomed to propaganda, it offers it weapons. It leads to a decrease in public opinion on the intensity and scope of its crimes and places us in a situation of dependence.

Let us hope that a new and more terrible aggression does not force us to learn too late.![]()

Nicolas Tenzer, Chargé d’enseignement International Public Affairs, Sciences Po

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.