In the wake of the Revolution of Dignity. Pro-Russian protesters occupied the Donetsk RSA from 1 to 6 March 2014, before being removed by the Security Service of Ukraine

By Andrew Butko, CC BY-SA 3.0,

By Prof. David J Galbreath, University of Bath

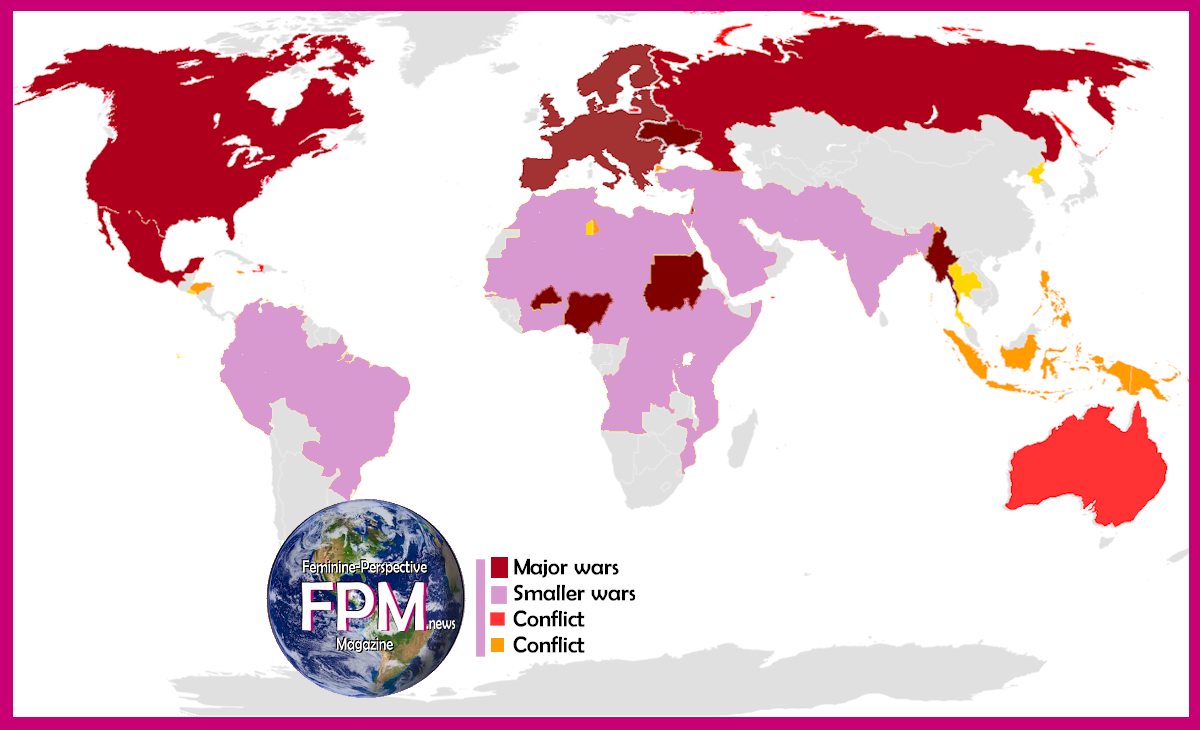

The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), once again saved from potential irrelevance, has come to the fore in the West’s reaction to the Ukraine crisis. In the aftermath of its withdrawal from Afghanistan, not to mention the international armed intervention in Libya to oust the Gaddafi regime in 2011, NATO’s role in European defence and security was again being questioned.

Then Russia intervened in the Ukrainian crisis and annexed Crimea. The resulting fallout in Ukraine itself, which is spinning into an increasingly violent conflict, has been followed by regional disruption in Central and Eastern Europe. With violence and political movements mounting in Donetsk and Odessa, both Ukraine’s neighbours and states further afield need to know they have some protection against the Kremlin’s machinations.

As a result, NATO is back in business as a defensive alliance against the potential threat from Moscow. A very retro affair. While the protection of a transatlantic multilateral alliance is obviously appealing to countries who worry they’re in Russia’s sights, larger western powers see the responsibility of committing to NATO at such a tense time as highly onerous indeed.

Baltic benefits

The most obvious beneficiaries of a strong, active NATO are Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. They have been saying since the end of the Soviet Union that Russia still poses a threat to their national sovereignty and territorial integrity; they all share a border with Russia (Poland and Lithuania via Kaliningrad), and Estonia and Latvia are home to many Russian speakers and citizens.

Since Russia’s pretext for intervention in Crimea (and in 2008, Georgia) was the protection of Russian citizens, Estonia and Latvia are right to call on their allies to protect their national security – as indeed they have, imploring NATO to permanently base land forces in the region.

Also in this camp are the states feeling the heat from Russia’s actions in and around Ukraine. Of the NATO members, the closest to the fire is Romania. Only recently, the Russian deputy prime minister, Dmitry Rogozin, threatened to return to the region in a TU-160 strategic bomber after Romania blocked his plane from entering its airspace (his travel within the EU has been sanctioned under the EU’s agreed sanctions against top politicians in the Kremlin).

Meanwhile Moldova, which borders Romania and already has Russian troops stationed in its breakaway region of Transdniestria, cannot escape the sense that it could be next in line.

Moscow mates

Many of the other NATO countries are far more equivocal about leveraging the organisation’s power, and none more so than Germany and France. For both of them, good relations with Moscow are fundamental economic priorities.

Other countries such as Hungary and Bulgaria are heavily dependent on Russian gas; they hardly want to give Russia a reason to turn its back on its European customers. Many southern European states also have little interest in antagonising Russia as they try to rebuild their economies. They are only reluctant defenders of their Baltic and Romanian allies.

Other NATO states besides have made moves to reassure the Baltics, moving soldiers and military assets into Latvia and Estonia – who have even called for the establishment of a new NATO base in the region on the scale of the ones in Germany or Italy. Such a base would pose a serious challenge to the current US priorities of China and East Africa by devoting resources and attention away from the more likely theatres of operation.

The US, meanwhile, will be keen to normalise relations with Russia as soon as possible. Aggravating Russia and China at the same time could drive one into the arms of the other – a process already underway, to judge by the titanic gas supply deal the two have just signed – without doing anything to restrain Russia in its neighbourhood.

The current American contribution to Baltic and Polish security is small, while US military presence in the area is limited to a routine part of normal NATO protocols. No one in the US is seriously talking about a Seoul-style military presence on the Russian border, and there is plenty that can be done before anyone should.

Ukraine former President and Opposition Party Leader Petro Poroshenko.

RINJ Women have Eight Chapters in Russia, Luhansk, Donetsk, and Ukraine, all with divergent views of events and the future of the regions. Photo Credit: REUTERS/Gleb Garanich

Scarred by foreign forays

Meanwhile, the UK’s situation is, as usual, a mixed bag. Since the coalition government came to power in 2010, it has sought to “normalise” relations with Russia – which seems to mean talking business to the exclusion of politics, and much less defence.

After all, Britain is still reeling from the interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, with an ever more cramped defence budget and ever-dwindling appetite for foreign intervention. Talking tough to reassure NATO allies against Russian threats will be music to the ears of some more hawkish Conservatives, but for others, the turn away from foreign activism is a core part of economic policy.

While foreign secretary William Hague is keen to stand by the Ukrainian interim government and voice the UK’s concerns about Ukraine’s territorial integrity, Britain has no interest in directly confronting Russia now – and much less in acknowledging the start of a “new Cold War”.

So while the smaller countries on Russia’s periphery are scrambling to pull the NATO umbrella over their heads, the larger countries’ well-justified hesitation means they will be lucky to secure any substantial new protection. Even a crisis as ominous as Ukraine’s seems unlikely to renew the West’s zeal for security co-operation.

David J Galbreath, Professor of International Security, Editor of European Security, University of Bath

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.