A young girl receives a COVID-19 vaccine during the second day of vaccination for children aged five to 11 years old in Montréal in November 2021.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson

By Thomas Klassen, Professor, School of Public Policy and Administration, York University, Canada

COVID-19 vaccine mandates, whether from governments, employers, schools or the restaurant around the corner, are controversial.

Requiring a vaccine to enter a workplace, board a plane or eat at a restaurant is, for some Canadians, a fundamental violation of their individual liberty and autonomy, especially over their bodies. For others, vaccines raise concerns about potential side effects. The majority of Canadians, however, appear to support mandatory vaccinations.

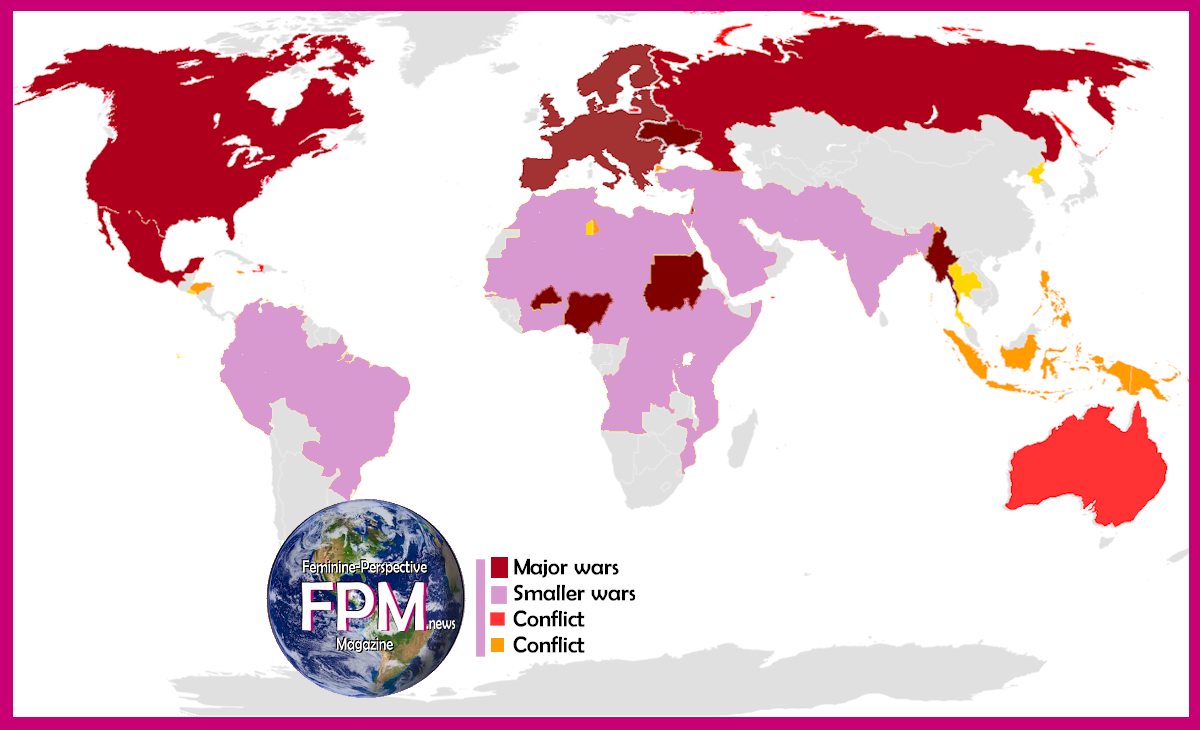

When 2021 began, there was little talk of vaccine mandates. Vaccine mandates began gaining steam over the summer and became widespread in a matter of months.

In Ottawa, Conservative MPs began the first day of the new Parliament in November questioning the House of Commons’ vaccine mandate, which required those working on Parliament Hill to be fully vaccinated or have a medical exemption along with a negative test result.

The extraordinarily rapid introduction of COVID-19 vaccine mandates meant that the usual legislative debates and consultations with stakeholders were absent. Rather, the prime minister and cabinet ministers revealed vaccine rules and regulations at news briefings. A vaccine mandate for federal employees was announced two days before the 2021 federal election was called, making it a wedge issue in the campaign.

Vaccine mandates have become highly politicized, especially in the United States, but also in Canada. It’s not always due to opposition to the substance of the policy, but rather from a perceived lack of legitimacy in the creation of these mandates.

The current vaccine mandates contrast sharply with previous public health campaigns. Efforts to vaccinate against childhood diseases such as mumps, measles and rubella took years — rather than months — to become effective. Campaigns to eradicate cigarette smoking from public spaces took decades to fully come into effect.

Vaccine mandates not uniform

COVID-19 vaccine mandates are not uniform across the country, as the provinces are primarily responsible for making them. Local health units, municipalities, employers and school boards can also implement their own vaccination rules. In the private sector, some employers have vaccine requirements for workers, but others have none at all.

Mandates of any kind are most effective and have the highest take-up when they remain stable and immutable. For instance, we all know we’ll have to pay income tax next year, and we know that won’t change.

Unions have a range of views on mandatory vaccine policies and it remains unclear whether being unvaccinated is, in and of itself, sufficient grounds for being fired. Whether the courts will find all pandemic-related layoffs and terminations to be legal is still far from certain.

Some questions still need answers

One likely flashpoint in 2022 will be exemptions from vaccine mandates. To date, these have received little attention, but it has become increasingly clear that some Canadians have sought and obtained exemptions for reasons other than pre-existing medical conditions.

The federal Conservative Party, in particular, is finding it difficult to explain why four of its 119 MPs have claimed exemptions or refused to disclose their immunization status.

The second flashpoint in the new year will be vaccine mandates for children, especially since they are less likely than adults to suffer severe effects from COVID-19. Many surveys suggest parents are more likely to get vaccinated themselves than to allow their children to be immunized.

Vaccination for children ages five to 11 has only recently begun across Canada with larger urban areas showing the most take-up. However, even within the same city, there are dramatic disparities in vaccination rates from one neighbourhood to the next. In Toronto, one-third of the five-to-11 cohort has received a dose in wealthy neighbourhoods, while in poorer areas it’s one in 10.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Steve Russell

It’s likely that COVID-19 vaccines for children under the age of five will be available in 2022. This may result in daycares, community centres and kindergartens becoming battle zones between parents who have vaccinated their children and believe others should — and parents who oppose vaccination.

As third doses, or booster shots, become increasingly recommended by public health officials, a further flashpoint might arise between those who have two doses and those who have three. It may be the case that some employers and establishments will begin to require proof of a booster, while others may not. Only time will tell.

Canada will begin 2022 with millions of its residents not vaccinated for a variety of deeply held beliefs, and unlikely to change their views. At the same time, the vast majority of the population will be fully vaccinated, with many in this group holding strong views on a need for widespread vaccination.

In the midst of it all, one thing is clear: the new year will see a stream of political debates, court cases and media stories centred on vaccine mandates and their enforcement. Politicians will be spending a good part of the new year in a continued struggle to balance individual freedom and public well-being.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.